What follows is the text I used as my guide during my 2016 Open Source and Feelings talk When the Worst Happens. You can also view a video recording of the talk. [Link added 26 August, 2016]

Some housekeeping to get us started. First, I have cough-variant asthma. I can usually get through a shorter talk like this, but just in case I want you to know that if I’m over-taken by what sounds like a very bad cough, I’m okay. I’ll just step to the side here, cough my way through it, and then return. Hopefully if it happens we can crowd-source some jokes or maybe Utah could dance a jig.

Second, a few content warnings. I’ll be mentioning suicide. I’ll also touch upon issues around burnt out, mental health, housing instability, and other ills of capitalism. Please do what you need to do to take care of yourself and feel free to step out at any time. I’ll be sharing my slides and a transcript afterwards, so you’ll have a chance to catch up if and when you’d like.

And, I’ll take questions at the end, if time allows, or during the break.

In Portland, we run a conference, some of you may have heard of it, Open Source Bridge. We call it the conference for open source citizens. We focus on participation, connection, and inclusiveness across the open source community. I co-chaired the conference for five years. This year was my first having no official job other than letting everyone else do theirs without butting in. It was wonderful. For me, it was incredibly rewarding to be able to step back from something I’ve invested much of my heart into and see others continue the good work without me.

I also helped start a non-profit called Stumptown Syndicate. The Syndicate works to bring tech and maker skills to communities in ways that enable positive social change. Through my work with Stumptown Syndicate, I’ve also helped organize many other tech gatherings, including BarCamp Portland. I am also co-author of the Citizen Code of Conduct.

Somewhere in the middle of all this organizing a few colleagues and I thought it would be a good idea to share what we’d been learning. So, we put together a book and workshop on how to organize community tech events.

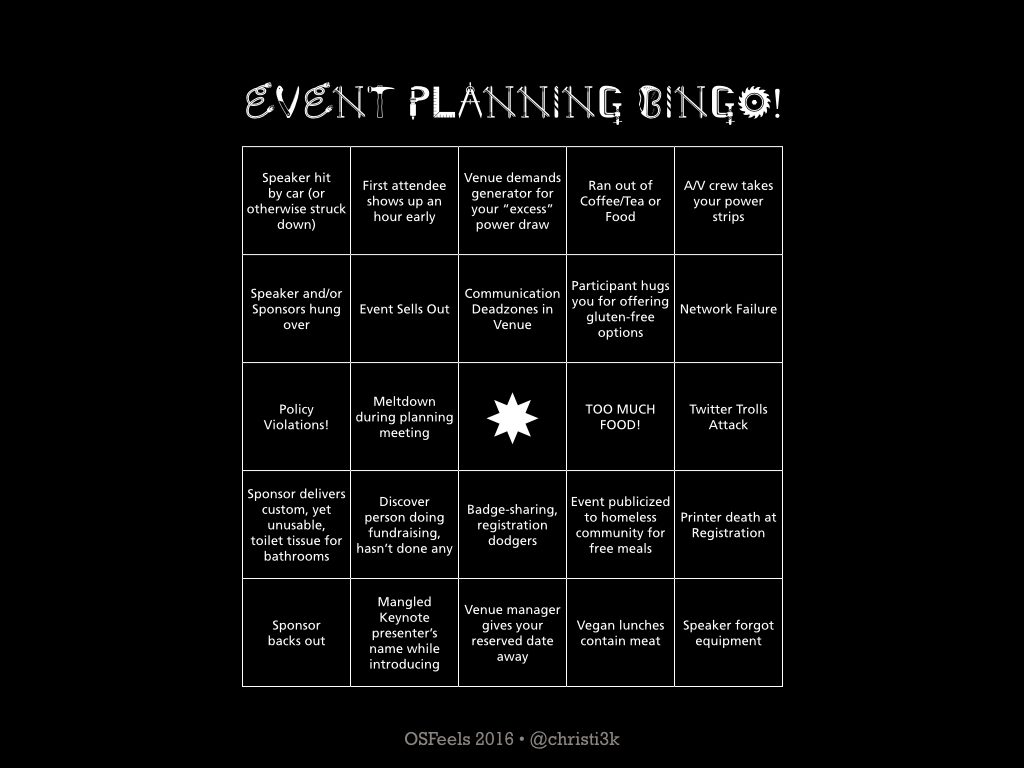

Like all good workshop materials, ours included a bingo card of things that could go wrong.

Each of these squares describes a problem we have directly experienced as organizers or as attendees. If you don’t already know about the branded toilet paper at OSCON that one year, all you need to know is: DON’T. Just no.

You can tell I haven’t updated this card in a while because otherwise it would have a square for “food-borne illness outbreak”, which is something that happened at Open Source Bridge last year.

The point of this card is to show that yes, things will go wrong. And that often the things that go wrong won’t be what you expected or prepared for. By putting all these things that can go wrong on one card, we wanted to demonstrate that you can survive the bad stuff and become stronger for it.

Or, at the very least you can shout BINGO at some point.

There’s another square is missing from this card. I’m not sure I will add it because it turns out it’s probably the hardest thing to deal with both as an individual organizer and as a community. If it were to be included, it would be an entire bingo card on its own. And probably in too poor of taste. I’m speaking of the unexpected death of a key organizer.

In 2013, a few days before we were to send speaker acceptances and finalize our schedule for Open Source Bridge, Igal Koshevoy, one of our key organizers and someone who’d worked on Open Source Bridge since its beginning, took his own life.

Those closest to Igal knew about his struggles with depression and social anxiety. He had been withdrawn from the community for months. Welfare checks had been requested and performed.

And yet, you are never prepared for this kind of loss.

Igal died in early April, 10 weeks before Open Source Bridge was scheduled to begin. Contracts had been signed. Tickets had been sold. We had to notify speakers and publish our schedule.

We had no choice but to move forward. To make the conference happen. To help settle the affairs of our friend. To navigate our grief. And, most of us had day jobs and families to attend to as well.

We managed to keep the conference more or less on schedule. Open Source Bridge year 5 happened. It went as well as it ever had. We had a big party at the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry where we celebrated our 5th anniversary and we celebrated Igal.

While writing this talk, I tried to figure out exactly how we kept everything moving. I couldn’t. I looked through the archives for our email planning list. The messages don’t look substantially different from any other year. We cancelled exactly one planning meeting, the week of Igal’s death.

I think we were able to do this because we had a lot going for us, relatively speaking. It was year five of the event, not year one or even two. We weren’t in a significant transition year in terms of team members. And our core team is really dedicated.

We also were supported by the Portland tech community at large.

While we planned our conference, we also organized a\celebration of life for Igal. This is how I learned that it turns out a lot of the skills you use to organize tech events also apply to memorials. As they often did with so many of our events, the Portland tech community came together to help. The folks who we’d been convening with for years at barcamps, user groups, and other events pitched in here and there, in small and big ways to help make Igal’s celebration happen.

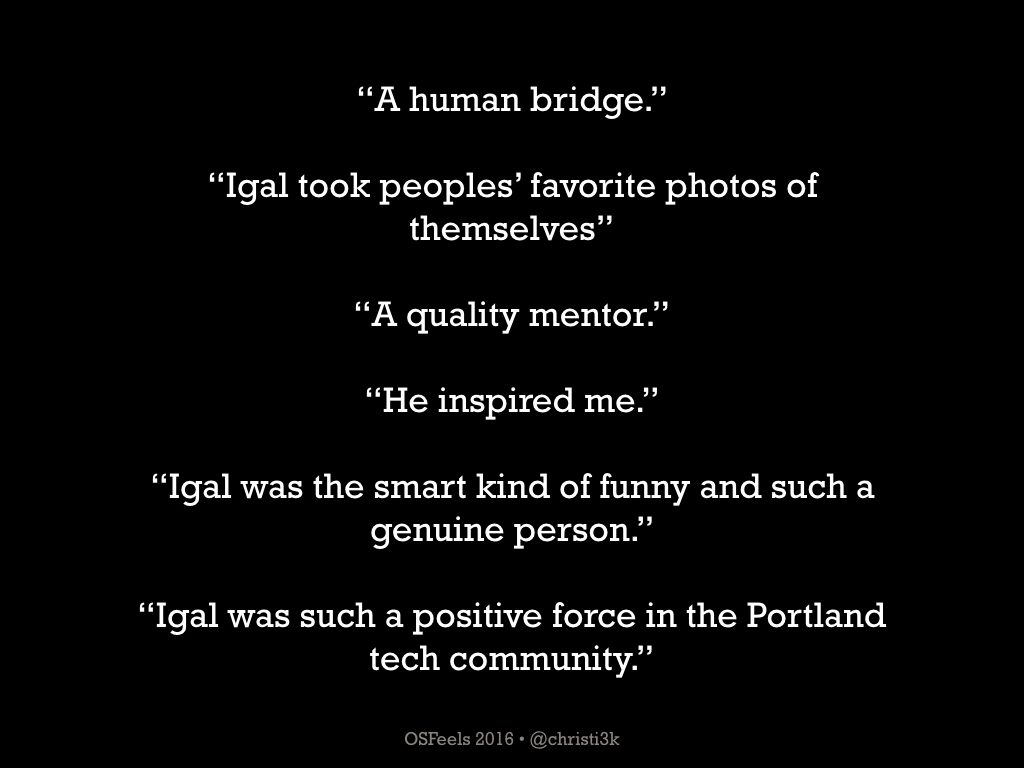

It turns out that for a lot of people, Igal was one of their first connections to the Portland tech community. It was his warmth, his presence, his dedication, that helped bring people into the community and feel welcome.

These are just a few of the things folks said about Igal upon his passing:

This was certainly true for me. I moved to Portland in Fall of 2007 and Igal is one of the first folks I distinctly recall meeting. Actually, I encountered Igal first on twitter and I was kind of intimidated by him because of his avatar:

Do you ever have this experience? You meet encounter someone, either on twitter, or in person, and your impression of them is, “too cool for me!” or something similar? It makes me wonder what people’s first impression of me is…Anyway…

I saw Igal’s avatar and, this is embarrassing, I thought, damn, this dude can bench press hundreds of pounds. And can probably light objects ablaze with a single glance!

Once I met him though I quickly realized my impression was a little off. Although very resourceful as a former eagle scout, Igal wasn’t at all scary or intimidating. He was warm, friendly, and dedicated to serving the community. He loved cats. He went out of his way to see that people had what they needed. He spoke several languages. He used to take and share the most amazingly detailed, useful notes.

Once he explained to me his process for creating these notes, I never again took note-taking for granted again. For Igal, it was complicated and time consuming because the language of his thoughts, the one his mind used to process, was not English. So, he had to translate twice, once upon hearing the information and then again upon writing it. That was Igal, though. He would do the work even when it took twice the effort if he though it would be helpful.

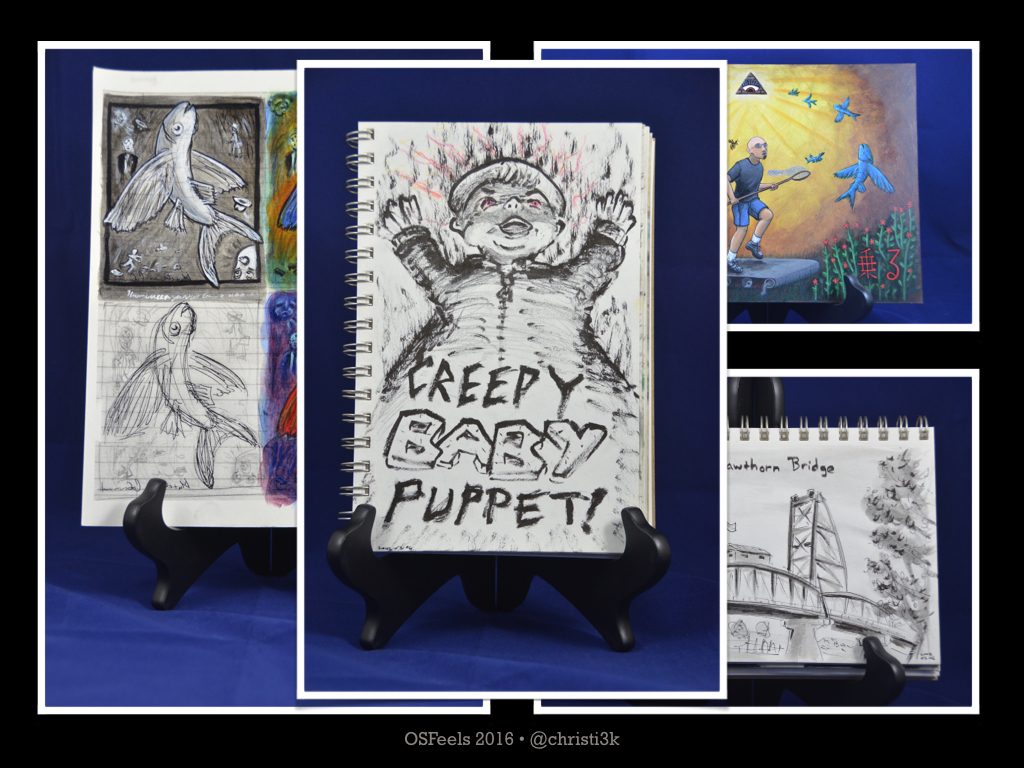

Igal also created beautiful art. Although some of it was a little weird, in a funny way.

And Igal struggled, the extent to which is something I learned only after he was gone.

My impression of Igal changed significantly from when I first met him to after I got to know him. And it evolved further when I learned things about him after he passed.

I call attention to these disparities for a reason.

We often project ideas about the organizers in our communities that aren’t necessarily true. We project that they feel empowered by the power we place in them. We project they feel like they can ask for help because we are willing to provide it if asked. We project that they know they are appreciated because we feel appreciative of all that they do. We project that they are doing okay because we see them getting shit done. We project that they feel loved because we love them and all they do for us. We project that they can set objects ablaze with a single glance because they have a stern twitter avatar.

While holding leaders accountable is important we also have to recognize that we need to build systems and communities that allows leaders access to self-care and respite and appreciation and support as they need it.

In addition to planning our conference, and a memorial for Igal, we worked to safe guard our community’s assets that had been in Igal’s possession at the time of his death.

Because Igal was so involved in the activities of Portland Tech, he actually own or controlled a lot of our communal assets too. Mostly this included things like domains, code, and hosted applications.

In our case, we were lucky, if you can call it that, on multiple counts. Although Igal attempted to leave a will, it was not legally valid. We were able to transfer all of the community’s assets that Igal had been hosting because: a) Igal left us with al his passwords and login details, and b) By this time we had already created Stumptown Syndicate and so we had somewhere appropriate and uncontroversial to migrate things to. And his next of kin was cooperative.

Igal didn’t host all of these things for us to be controlling or to concentrate power, but rather he did it out of a sense of service and to provide convenience. I think this is true for a lot of our community work. You get together to write an app to do a thing. When it’s time to deploy someone creates a droplet or a vm or a vps or whatever’s en vogue at the time and you get up and running.

I think if we were to take a census, the majority of our small group work product in open source is probably technically owned or at least controlled by individuals.

Think about your own community’s work. Who owns the accounts under which things are setup? Who has access to these accounts? Does they have access because of shared login credentials, or have they been made an authorized accessor? What would happen to these accounts and whatever assets they hold if the owner were to die unexpectedly?

The laws on this vary by location, but generally if the person hasn’t left a valid will — and many people do not have valid wills — then ownership/control falls to the person’s next of kin. Is that person going to be available? Accessible? Cooperative? how many of you have tried to explain open source to your relatives?

This issue is relevant not just to community assets, but to you personal body of work as well. If you care about how your work is used and where any proceeds generated by your work should be directed after you’ve passed, you need to account for that in your estate planning.

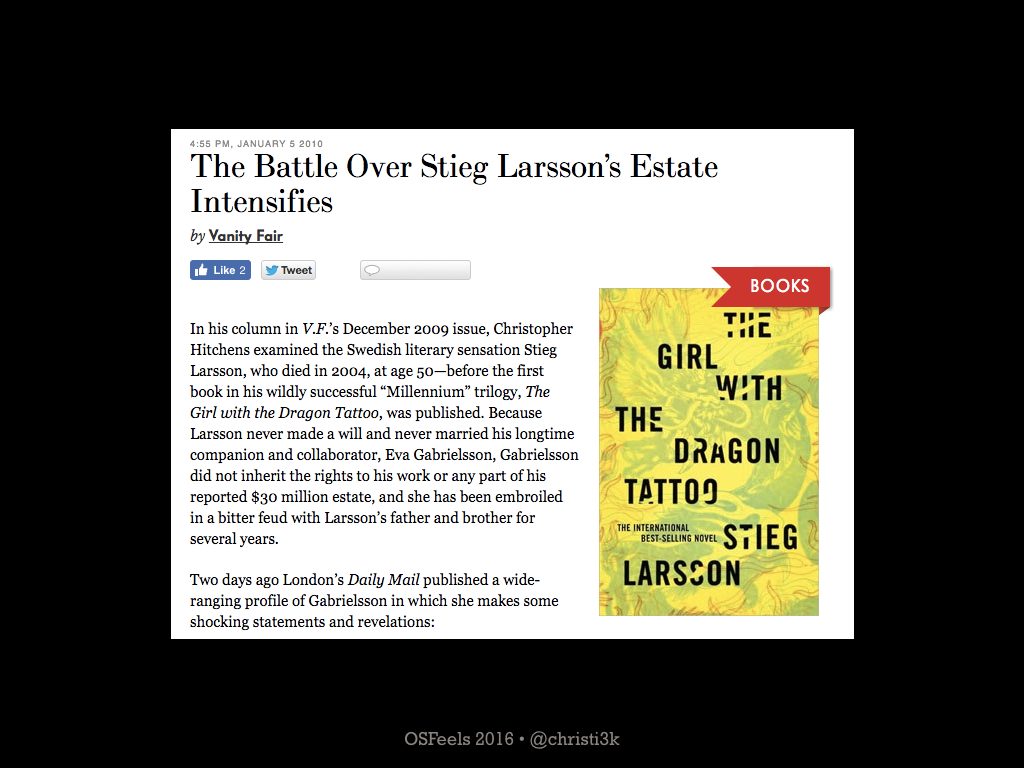

A while ago Neil Gaiman noticed that authors had a similar situation in that it was common for authors to pass on without having a will in place that explicitly outlined their wishes with regard to their intellectual property. Not having this document quite often created conflict among surviving friends and family members, and/or an outcome the author clearly would not have wanted. When I read Neil’s post I immediately thought of Stieg Larsson.

I’m guessing we have some Girl with the Dragon Tattoo fans here, so some of you may know about this. Larsson’s wildly popular Millennium trilogy was published after his sudden death from a heart attack at age 50. Like Igal, Larsson left a will but it was not legally valid. As a result, Larsson’s estate, including control of his literary works, fell to his family members, and not his long-time partner Eva Gabrielsson. And that’s why we have a fourth Lisbeth Salander book not written by Larsson.

And so Neil worked with an attorney friend of his to create a boiler plate will that explicitly covered an author’s intellectual property.

I think we need something like that for open source work.

It’s been a little over three years since Igal passed. I no longer feel the same acute pangs of grief that I did then, although I occasionally think I’ve spotted Igal out of the corner of my eye and a split-second of joy gives way to a dull ache of sadness and regret.

Looking back, what I regret most is not spending more time just hanging out with Igal while he was with us. Outside of the few annual holidays that Igal celebrated with us in our home, most of my interaction with Igal happened in the content of our open source community work.

This pattern isn’t specific to my friendship with Igal. I’ve built a lot of friendships based around work. Actually, until recently, I’ve built most of them around some kind of “work.”

Some of this is Protestant culture and work ethic. I grew up in a family where work was paramount and play was discouraged and sometimes even punished. I learned early on that in my family, volunteering was one of the few permissable way to socialize with others. And, it often made accessible to me activities that were otherwise out of reach because of our economic situation.

Open source greatly benefits from people like me who are conditioned to seek out extra curricular work projects and volunteer opportunities and so it is rewarded and encouraged. Indeed, open source thrives on the line between vocation and hobby being as blurry as possible, because open source is dependent on a steady source of free labor. This is a problem because there are very few, if any, mechanisms for monitoring contributor well-being.

Why is this so and what does it mean for our movement?

Well, what do our FOSS forebearers have to say about this? It turns out, not much. They have focused, for the most part, on the intellectual property rights, the licensing aspect, of open source.

For example, the Free Software Foundation is primarily concerned with user freedom and does much of its work via GPL enforcement. GPL being the “GNU Public License,” which they created.

The Open Source Initiative has made it its business to determine what licenses even qualify as open-source.

The few organizations, such as Apache Foundation, that are focused on individual developers are concerned mostly with infrastructure and with ensuring the production of open source software continues, rather than contributor and community well-being.

What these approaches lack, and it is a serious omission, is recognition that open source is as much a mode of production, as it is a matter of intellectual property rights. By “mode of production” I mean the combination of labor and the materials, infrastructure, and knowledge required to make and distribute things. In the case of open source, we’re generally talking about software, and sometimes hardware.

What are unique characteristics of open source software production?

The labor is a mix of paid and unpaid. Labor tends to me geographically distributed, with many working in nontraditional office environments during non-traditional work hours. There is no professional body governing entrance into open-source. Or ethics, or continuing education. For the most part if you have the skills, or the gumption to learn them, and access to a computer and Internet, you can start producing. The materials and infrastructure are provided by mix of individuals, foundations, and for-profit companies. Material input and work product is shared by partners and competitors alike. Because a major advantage is being able to use the prior work of others, Open source tends to favor interoperability and standards compliance. And because contributions of code are among the easiest to track and therefore make visible, “merit” is assigned disproportionately to technical contributions and technical roles tend to be valued above all others.

All of this sounds like open source as a mode of production greatly favors the individual worker. And there are many aspects of open-source culture that is very empowering. You can contribute from nearly anywhere. You can generally take share your portfolio as you move through your career. People with no formal training whatsoever can become prolific open source contributors. With an inexpensive laptop and access to the Internet you can create and share software without prohibitive licensing fees.

This last reason is why got into open source. It wasn’t ideology. It was economics. What mattered to me at the time was “free as in beer” not “free as in freedom.” As time went on and I gained some financial stability and started participating in open-source I got more into the ideology. It seemed to explain why I felt so good being part of the open source community. Not only was helping to build something greater than myself, but I was helping a righteous cause. Free software felt righteous.

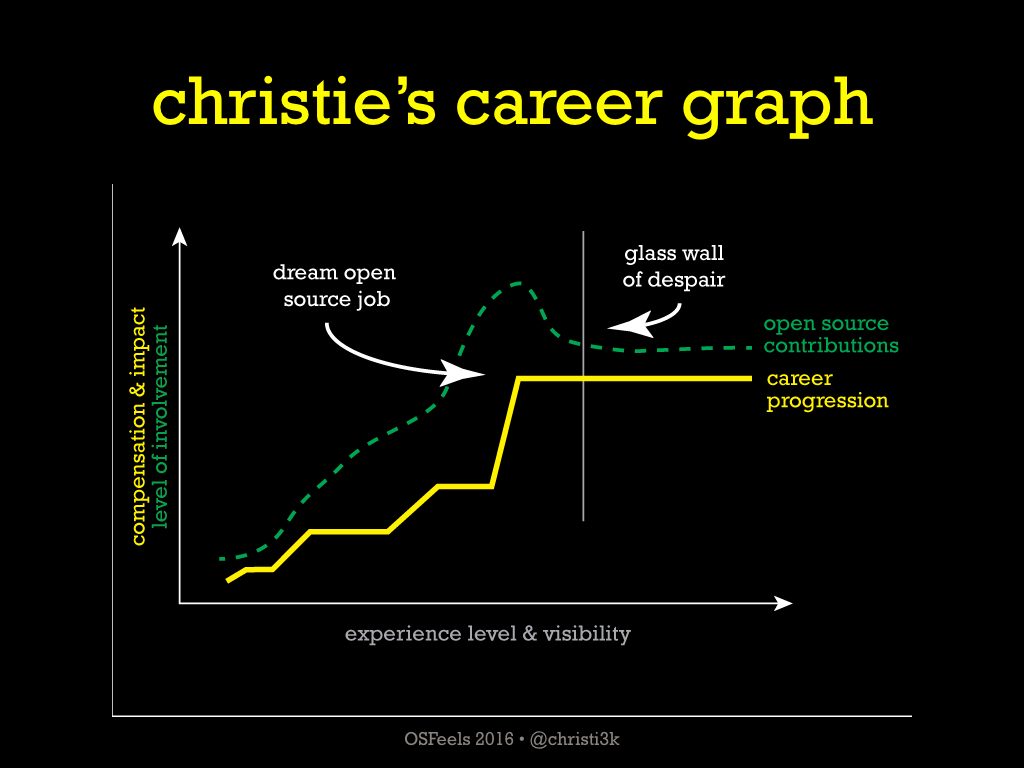

And for a time, I thought contributing to open source giving me a unique career advantage. For several years, as I became more and more involved and visible and open-source, I got better, higher paying jobs. Eventually I even got my open source dream job, at Mozilla.

But it turned out my open-source dream job wasn’t all that dreamy. While a highly visible and often looked up to the organization, Mozilla is highly dysfunctional. And it’s socially regressive particularly when compared to many of its peers in the tech Industry.

During the time I struggled at my dream job I watched friend after friend hit their own glass walls of frustration and burnout. I watched them run out of patience waiting to be appreciated and recognized for their technical acumen. I watched friends struggle over and over again to meet their basic needs for housing, food, and healthcare.

I observed in myself a struggle to balance my increasingly complicated health and family needs with my open source community obligations. I struggled to understand why I was unable to effectively apply my extensive open source experience at my dream job Mozilla. All the while I was growing weary and really wanting to break from unpaid volunteer work in order to explore other life pursuits.

Loosing Igal, watching people I care about struggle, and facing my own disallusionment, prompted me to start thinkingcritically about open source and how current norms and practices affects individual contributors and our communities. I’m not the alone in this. Many of us are starting to have these conversations.

Here’s where I am in my analysis.

There are two significant downsides to open source as practiced today.

The first is that organizations disproportionately benefit. How? Three ways.

ONE: They profit from the aggregate of our free labor. The sum of the free labor that we collectively give to organizations reduces their cost of production, and thereby increases their profit margin. And they are under no obligation to redistribute any of that profit or to recognize the economic value of our labor in any other way whatsoever.

TWO: Organizations have more power than individuals working alone. There are a few exceptions to this, like if you’re Linus Torvolds and you hold the copyright to something like Linux. But generally speaking, large open source projects, or even medium-sized ones, face little to no consequences for dysfunctional behvior because they easily withstand it when folks stop contributing here and there. At worst, the organization will actually have to hire someone and pay them a salary to do the work of an unpaid contributor who has left.

THREE: Organizations have a better chance at sustainability because they have greater access to capital to invest in product research, development, and distribution, which in turn generates greater profit. They have greater access to capital because they have access to investors and because they have a cheap labor source (us).

The second significant disadvantage to open source today is that individuals, on aggregate, disproportionately suffer. How? Three ways.

ONE: The economic value of our labor is made invisible. This is bad because it contributes to underemployment and underpayment. We might think we’re getting good resume-building experience — and for folks brand new to tech this might be true. But it has significantly diminishing returns. Most companies won’t pay for things they know they can get for free.

TWO: Open source promotes building community and social relationships that are fundamentally fragile, unaffirming and extractive. This is because open source transforms what should be our third spaces — places that are anchors of community life like the neighborhood coffee shop, the community center, the local church, and so on, into work places. The problem with this is that it brings work-type stress into our personal relationships. It keeps those relationships one-sided, bound if not to professionalism directly, but to a directive to always be getting things done. It squeezes out the space to simply play together. Relax together. Be together.

THREE: An empasis on consistent technical contribution as a requirement for inclusion reinforces the idea that we are only as valuable in so much as we are able to contribute. If we become unable to contribute, either in the short term or the long term, of if we were never able to fully participate in the first place, it can leave us feeling worthless. Our value as human beings and our right to be included in our communities shouldn’t be contingent on an on-going ability to consistently make technical contributions. We are so much more than that.

The title of this talk is, “When this worst happens.” On a micro-level, it’s above the challenges our community faced when loosing one of our core organizers. On a macro-level, it’s about how we’re all participating in a system dependent on an ever-steady stream of contributors who give as much as they can, often without any monetary compensation for their labor, until they can’t give any more. Not being able to give any more means different things for different people. Some face emotional and physical burnout. Some have to take paying jobs outside of open source. Some can’t find paying work even with their extensive open source experience. Some decide that the pain of this world is too much and decide to leave it like Igal did.

When I criticize open source culture, I’m not arguing in favor of proprietary licenses. I think the less restrictive intellectual property rights are, the better society is as a whole. Rather, I’m arguing that we need a better model of free and open source software. One that prioritizes our humanity. One that helps meet our needs for food, shelter, and security. One that helps us build communities that realize everyone’s potential, whatever that may be. One that contributes towards the building of a better future for us all. The four freedoms are meaningless if people don’t have enough to eat, clean water to drink, a place to live, or adequate healthcare for mind and body. They are meaningless where trans folks don’t have a safe place to go to the bathroom and where black lives don’t matter.

“When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights are considered more important than people,…the giant triplets of racism, materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered.”

I came across this quote while reading the other weekend and it shocked me how contemporary it felt. Does anyone recognize it? Martin Luther King said this in 1967 about the Vietnam War.

What do I want you to take away from this talk?

One, ensure your community’s assets are safeguarded. At the very least, document where everything is and how to access it. For bonus points, set up something to handle significant transitions.

Two, ensure personal body of work is safe guarded by creating a will, one that specifically covers your digital and creative work.

Three, build community in well-rounded ways and help restore our third spaces. Think of yourself more like an ecumenical community center than a user group or open source project.

Finally, join me in building a better, more sustainable model. One that recognizes and fairly compensates everyone’s labor and reinvests into our communities. Think of starting co-ops and benefit corps, rather than vc-funded 10x startups or even traditional foundations.

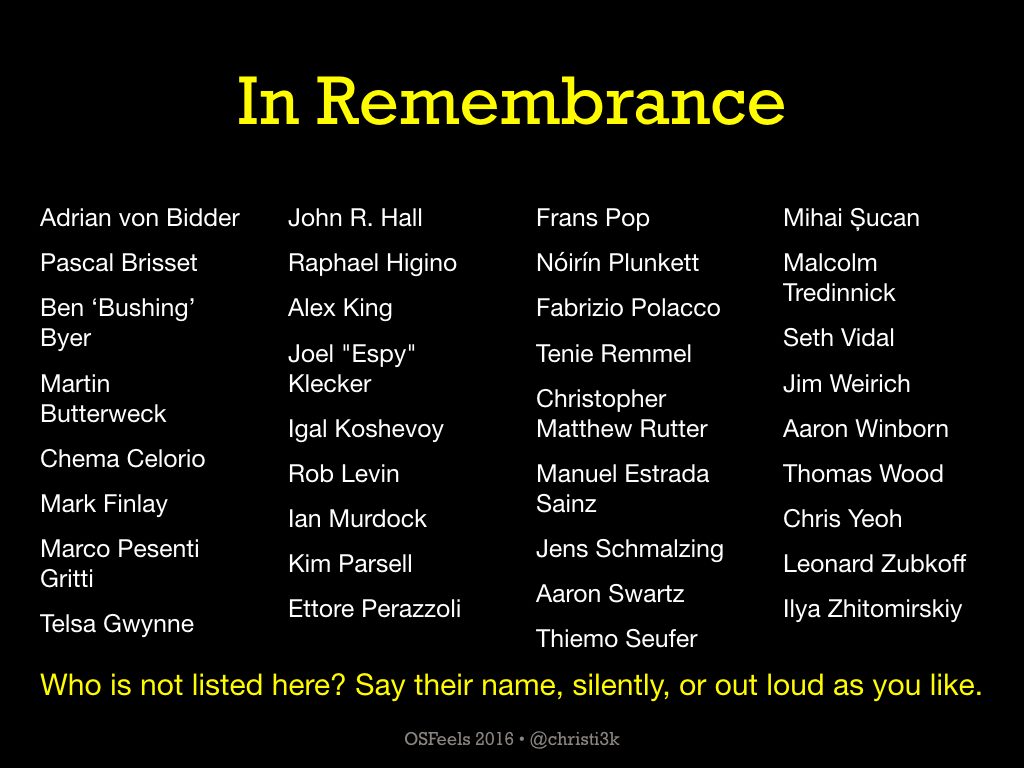

During the last couple of weeks I’ve been asking for the names of folks we’ve lost before their time.

They are listed here so that we may honor them now. I know this list isn’t complete, though. Please add any name that’s missing now, either by speaking it silently to yourself, or out-loud as you like.

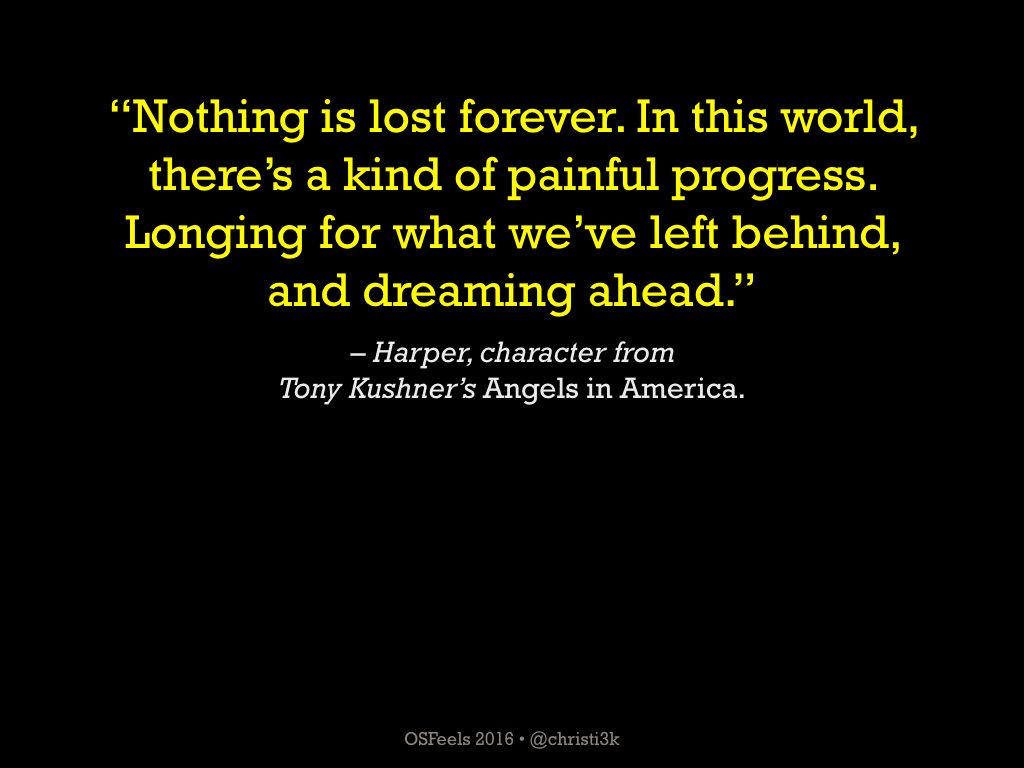

I feel like this has been a heavy, dreary talk. So I want to leave you with some words of hope.

Angels In America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes, is one of my all-time favorite plays. It’s a massive work about AIDS and queerness and 1980s America. One of the issues it grapples with is how to make sense of loss. This quote is from the monologue that closes the play, it goes like this:

“Night flight to San Francisco. Chase the moon across America. God! It’s been years since I was on a plane. When we hit 35,000 feet we’ll have reached the tropopause, the great belt of calm air. As close as I’ll ever get to the ozone. I dreamed we were there. The plane leapt the tropopause, the safe air and attained the outer rim, the ozone which was ragged and torn, patches of it threadbare as old cheesecloth and that was frightening. But I saw something only I could see because of my astonishing ability to see such things. Souls were rising, from the earth far below, souls of the dead of people who’d perished from famine, from war, from the plague and they floated up like skydivers in reverse, limbs all akimbo, wheeling and spinning. And the souls of these departed joined hands, clasped ankles and formed a web, a great net of souls. And the souls were three atom oxygen molecules of the stuff of ozone and the outer rim absorbed them and was repaired. Nothing’s lost forever. In this world, there is a kind of painful progress. Longing for what we’ve left behind and dreaming ahead. At least I think that’s so.”

I believe we are working towards that kind of painful progress. And, I like to believe the souls of those we lost are helping us to do that, still. I ask you now, let’s dream up a better future and start building it together today.

Thank You.

I forgot to include acknowledgements at the time I gave me talk, so I’ll do so now:

Thank you Sumana Harihareswara, Ed Finkler, and Amy Farrell for reviewing my proposal for this talk and encouraging me to submit it.

Thank you Chris Ball, Chris Koerner, Andromeda Yelton, Federico Mena Quintero, Chris Swenson, Damien McKenna, Floren F, Dan Paulston, and Davey Shafik for helping me compile names for the remembrance portion of my talk.

Thank you Sherri Koehler, my lovely wife, for staying up late on Skype to hear me reverse drafts of it.

Thank you Jeremey Flores and Kerri Miller for being super supportive of me giving this tough talk and for putting on an awesome conference.

Lastly, thank you Igal Koshevoy and Nóirín Plunkett for your friendship. Miss you both.